The Chinese style of doing business is becoming more Westernized. However, foreign executives still have to work hard to build trust with Chinese business partners.

Our main question

How to build effective business relationships in China today?

Solutions:

. Chinese business culture is changing as the country opens up to international companies.

. Western leaders need to instill confidence in their competence and capabilities among their Chinese partners.

. Trust based on empathy and personal contact is especially important for business relationships in China, but such relationships are difficult to establish.

An international car company entering the Chinese market followed what it considered to be local rules. Leaders knew that to build personal relationships you had to give gifts, and success in China depended on who you knew, not what you knew.

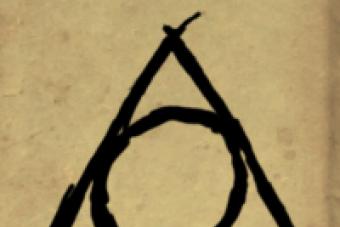

The company held special events and dinner parties to foster personal connections, including important guanxi, the Chinese term for personal relationships between people doing business. But after several years, the company discovered that the return on all its efforts was minimal.

Moreover, when company executives tried to understand why this was happening, it turned out that their concern had a bad reputation among potential Chinese industry partners. They believed that the international automaker was just a “seeker” of short-term business opportunities packaged in expensive entertainment.

The Chinese executives whom the company so carefully courted saw it as a source of free entertainment—and expected it in every interaction. To make matters worse, potential business partners began to believe that the company had no interesting business proposition because it did not appear to be business-focused. And although the company met the people it needed, it was never able to build critical relationships. As a result, her initiatives failed. This is a very common problem for foreign companies looking to establish themselves in China.

Myths of guanxi

In our studies of cross-cultural interactions, we found that Western managers have a fundamental misunderstanding of the meaning of guanxi. Experts are lining up to offer Western businessmen books, articles, courses and websites that will help them create guanxi. But all the advice from guanxi “experts” usually boils down to general words about friendship and family values and banal instructions like “keep your business cards ready.” By focusing on building relationships, experts tend to overlook the factors that make them fruitful. Typically, the concept of guanxi is distorted due to two misconceptions. The first misconception is ignoring the changes taking place in the Chinese business environment. China's rapid development and integration into the global economy is bringing local business practices closer to Western standards. The activities of Chinese regulatory authorities are becoming more transparent, and the legal system is also developing, which allows conflicts to be resolved more effectively.

These changes have led more Chinese companies to view gift-giving and other similar gestures negatively, preferring to focus on the business value that a potential partner brings (see Myths About Gift Giving). In this sense, guanxi is becoming more and more similar to the pragmatic networking familiar to Western leaders. Knowledge and skills, rather than acquaintances, are becoming increasingly important.

The second mistake is the use of crude tools of social etiquette and general ideas about friendship and family when building guanxi. Successful long-term business relationships in China truly rely on strong personal connections. In China, it is not customary to draw a clear line between business and personal relationships, as in many Western societies. But attempts to build guanxi using the methods that experts most often suggest to Western executives may turn out to be futile—as in the case of the car company. As an American executive in charge of branding in China said, “Too much focus on communication ends up devaluing the relationship.”

Although foreign entrepreneurs are aware of the importance of guanxi for business success in China, they receive little advice about what exactly makes business relationships with Chinese partners effective. I believe a new recipe is needed that translates pragmatic Western business relationships into the Chinese context and provides insight into how to establish effective relationships between partners across cultural boundaries. Trust can be built in two ways. In Western culture, it is customary to build trust “from the head,” while in China it is customary to build trust “from the heart.” Trust “from the heart” is not only different, but also more complex. In any case, if you want to build guanxi, you need to start with trust.

The Key Role of Trust

In research I and my colleagues conducted, it turned out that trust is the foundation of successful long-term cross-cultural business relationships (see “About the Research”). In cross-cultural business relationships, trust is essential because partners from different cultures may have different values or ideas about how the business operates. When trust is built, partners can resolve difficult issues through an open exchange of ideas and plans. Trust will also help solve the most serious problem that foreigners face when working with Chinese entrepreneurs: unpredictable behavior of partners and lack of transparency. “In China, success depends on how much people trust you,” says a Chinese Google executive.

To teach Western executives how to build trust with Chinese business partners, we must understand how trust is formed in American and Chinese business networks and what happens when different approaches to building trust collide. In our research, we looked at two types of trust. We called the first type trust “from the head” (cognitive trust). This type of trust develops from confidence in a person's skills, reliability, and achievements. The second type of trust, which we called trust from the heart (affective trust), arises from a feeling of emotional closeness and empathy and contact. Most friendships are based on trust from the heart.

Are there differences in how Americans and Chinese build trust in their business networks? To answer this question, we surveyed more than 300 Chinese and American executives from a wide range of industries, including information technology, finance, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing and consulting. We have found that Americans draw a fairly clear line between trust from the head and trust from the heart in business relationships. American executives are twice as likely to differentiate between these two types of trust as their Chinese counterparts. (For Chinese leaders, the correlation between these two types of trust is about 0.6, while for American leaders it is about 0.3.)

This difference in results is explained by the characteristics of Western culture and history. There is a long tradition in the West of separating the “practical” from the “emotional.” Mixing these two areas is perceived as unprofessional and increases the risk of a conflict of interest. For Chinese leaders, the relationship between trust from the head and trust from the heart is much stronger. Unlike Americans, the Chinese tend to form personal connections with those with whom they also have financial or business ties.

When trust crosses boundaries

The first findings raise a new question: How exactly does trust arise between Chinese and Western leaders? To find out, we interviewed top managers of Chinese companies whose foreign partners included both ethnic Chinese and non-Chinese. Through on-site interviews with 108 Chinese executives (mostly CEOs and other senior executives) who studied their foreign partners in depth, we found a deficit of heart-to-heart trust between Chinese executives and their non-Chinese partners. The study showed that partners with a common cultural background will inevitably have a common platform of values and norms, which will contribute to interpersonal understanding.

For example, one Chinese-Singaporean executive found that his Chinese heritage greatly helped him when he moved to Beijing, as he could participate in tea ceremonies. (The tradition of tea drinking is an important part of Chinese culture. Selecting, brewing and enjoying the taste of Chinese tea are complex rituals that have become an art form in their own right.) In China, business meetings are increasingly taking place in teahouses, but Chinese leaders are usually reluctant to involve foreigners in this experience. fearing that they would not appreciate him. After all, Western entrepreneurs doing business in China almost always lack trust “from the heart,” based on deep knowledge of the culture. The problem only gets worse when viewed from the opposite direction: native Chinese believe that Chinese ethnicity is stronger than cultural differences resulting from differences in parenting methods in different countries.

The trust deficit between Chinese and foreign leaders is less pronounced when it comes to trust based on competence and reliability. Representatives of the same status group (in our case, top managers) are often inclined to positively assess the competence of people equal to them in rank. If a potential business partner is also an executive at a well-known company, then in Chinese culture the default assumption is that he is competent and reliable. This can become the basis for the emergence of a trusting relationship.

Family and friendship are more than metaphors

One Italian venture capital executive told us bluntly that, in his experience, friendship matters little in Chinese business relationships. He constantly sees other foreigners smiling, but their efforts lead to nothing. In our research, we found that American executives are indeed more likely to develop trusting relationships with their network of friends than Chinese executives. This is due to the importance of family ties in China, where family relationships are contrasted with friendships. Chinese family collectivism is rooted in Confucianism, an ethical and philosophical system that has been the basis of Chinese culture for centuries. Three of the five most important Confucian models of behavior and harmony are associated with family and hierarchy and regulate the relationships “father-son”, “husband-wife”, “elder brother-younger brother”. These familial and hierarchical ties foster affective ties that are very different from friendship ties.

Americans, for example, often develop friendly relations with their bosses. The Chinese, as a rule, treat their superiors with admiration and reverence. The Chinese are less likely to be friends with their subordinates - and they certainly will not emphasize such relationships.

But while family is a central concept in the context of Chinese culture, Westerners often misunderstand the Chinese concept of family. “Foreigners' ideas about guanxi are too simplistic, because in the Western sense, a family is a small unit,” says a Hong Kong professor who is responsible for building partnerships at his university. - In China, people are close even with distant relatives. The idea of guanxi is much broader.”

It is helpful to think of the Chinese family concept as a template that can be applied to the many networks of relationships that hold society together. In the context of Chinese business, the concept of "family" is more than emotional support and connections between members of a nuclear family (that is, a family consisting of only parents and children). For example, family members rely on each other to resolve practical issues such as obtaining a loan or finding a job. In family relationships, trust “from the head” is mixed with trust “from the heart.” Because the concept of family is a template for a wider range of Chinese social relationships, Chinese business culture can comfortably combine these two types of trust. It is no coincidence that the Chinese word “xin-ren,” meaning “trust,” indicates both trust “from the heart” (xin) and an assessment of a person’s reliability and abilities (ren).

But even if you are aware that the concept of family is central to Chinese society, this still will not help you build business relationships in China. To do this, you need to know how and when to build both types of trusting relationships.

Two types of trust - and two stages of building relationships

Chinese business culture is changing as the country increasingly opens up to global companies. In particular, the Chinese are increasingly taking into account the competence and achievements of business partners. This means that Western leaders need to gain their partners' trust in their abilities. For Chinese companies and their executives, what matters now is the value a potential partner brings and the reliability of that value. This should be good news for Western leaders. Business relationships in China are now built from the same building blocks as in the US and Europe - business needs and confidence in each other's abilities.

A young UBS Securities partner we interviewed took advantage of these changes to build a network of contacts with future clients in China. He realized that Chinese executives did not always understand the securities markets as much as they would like. He builds relationships by providing them with information. “I noticed that if you demonstrate to your Chinese partners that you can be useful to them, they open up and gradually begin to trust you,” says a UBS top manager.

Another of our respondents, a young restaurateur, is absolutely convinced that in Hong Kong, too, building relationships must begin with building trust from the top: “If you don’t bring obvious value to someone’s network, you are likely to be ignored.” To generate this value, he regularly speaks at conferences and participates in industry events. As a result, potential business partners themselves seek contacts with him.

In many cases, the upfront work you do to show your worth helps build trust from both the head and the heart. One PR consultant recently experienced this himself. He was invited by executives of a multinational Chinese company to advise them on the company's growing presence in the American media. Arriving in China after a ten-year break, the consultant was amazed at how pragmatic business processes in the country had become, although, of course, there were plenty of dinners and other events this time too. During the business trip, which lasted one week, the PR consultant, together with the Chinese side, had to agree on the draft promotional campaign and sign a contract. However, negotiations stalled. If the negotiations had been conducted according to “Western” rules, the parties would have rewinded the discussion back to the point where the disagreements began and then would have taken a different path that suited everyone. However, a Chinese colleague of the manager with whom he was negotiating came to the aid of the PR consultant. The Chinese man, in a private conversation, suggested that he demonstrate “sincerity” in order to build stronger personal relationships with the head of the company. In other words, the Western PR specialist needed to work on the “xin” from the “xin-ren” bunch. Heeding the advice, the consultant began developing free samples of the press materials he would normally bill for. The Chinese company liked his approach, and this gesture on the part of the consultant allowed him to achieve such a level of trust that the parties resumed discussing the terms of the contract.

But it is not always possible to quickly establish trusting relationships. It may well turn out that you will have to work “without the counter on” for quite a long time. In this case, the Western partner may get the impression that he is being used. These fears are reasonable: in China, like in any other country in the world, there are mercantile people who use unethical methods. Each manager has his own criteria for unreasonable requests from a counterparty. But it's important to remember that it may take you a lot of time - and a lot of ideas - before Chinese partners consider you trustworthy.

The second stage is the development of the personal dimension

Given how much effort it takes to develop confidence in your own abilities, there is a high risk that by focusing on this, you will forget the importance of the personal dimension in the process of building trusting relationships. One of our respondents, an American branding executive, experienced this the hard way when he lost out on a $20 million contract. A Chinese baby products company approached the American company he represented to create a portfolio of new products. However, the companies had different views on the creative process. The Chinese wanted to generate as many ideas as possible and select the most successful ones, while the Americans proposed to first build a product innovation process and then manage it. The parties never came to an agreement, so cooperation did not take place.

Then the American leader took a bold step. He quit, moved to China and began developing a relationship with the company as an independent consultant. He studied the Chinese CEO well, he took a very pragmatic approach and began working with the company, modeling the innovation process and developing several prototypes. In this way, he satisfied the Chinese company's need for real results. The impressed Chinese signed a contract, assembled a team and appointed a technical leader from the company to it. But here again the problem with creativity surfaced, a tension arose between the focus on process and the desire of the Chinese side to quickly get as many new products as possible. The tension became so intense that the American consultant asked that the technical lead be removed from the project. To the surprise of the American, the CEO of the Chinese company, who sympathized with him, nevertheless refused to fire the technical director, citing the fact that they were from the same village. In other words, in China, trust in a partner’s abilities will never be stronger than affective ties. As a result, the Chinese abandoned the contract. After analyzing the reasons for the failure, the American consultant realized that he needed to be more patient when interacting with the technical manager. It was necessary to expand contacts with the manager so that he would have confidence in the product development process - and in the future result. How to expand such contacts? Western leaders who have mastered the art of building affective trust do so through a deep cultural insight that goes beyond simply internalizing social customs and etiquette. This deep knowledge helps bridge trust gaps by creating the conditions for the development of shared bonds and values among people from the same culture (see “Building Trust from the Heart Across Borders”).

One of the most powerful tools for understanding a culture is mastery of the language its speakers speak. In Chinese, as in English, one word or sentence can have different meanings. Realizing this, many Western companies are devoting more and more resources to language courses. Any Western executive facing a long business trip to China should enroll in such courses. At a minimum, Western leaders require excellent translators to ensure that no details are missed during negotiations. But you shouldn't rely too much on third parties. You are trying to build a relationship, your translator is not. Always keep all your partner's interests in mind and make allowances for his emotional state. However, knowledge of the language cannot replace a deep knowledge of the culture. As one Chinese managing partner of an international recruiting company noted, “People can communicate very well without understanding the other person's language. It's a matter of understanding the culture."

Such cultural knowledge is the basis for establishing trusting relationships “from the heart” - especially outside the office (and in China, a significant part of business contacts take place outside the offices).

Informal communication was a key factor in allowing the managing director of a large beverage company to build trust with his Chinese partners. He was sent from the USA to China to carry out major changes in the company's business. One of the first problems he encountered was the reluctance of his Chinese subordinates to openly question his ideas, which would help him come up with the best solutions. To get his employees to open up, he spent a lot of time outside the office getting to know their families, backgrounds and backgrounds. Like other leaders who successfully manage the personal aspects of business relationships, he knew that his knowledge must go much beyond the usual set of ideas about etiquette and customs. He had to demonstrate a conscious understanding of Chinese culture so that his subordinates felt that they were truly understood - and not perceived through the prism of stereotypes, “bought off” with gifts and adherence to etiquette.

When people feel that they are being judged based on incorrect assumptions, it immediately destroys communication. Imagine how Americans would feel if they felt that their European partners looked down on their culture. What will Europeans feel like if they suspect that their American partners consider them cultural chauvinists? However, in the Western model of business relationships, where personal connections are not so important, this type of tension does not particularly complicate business relationships. But in China, personal contact is an absolute necessity.

As Western executives continue to experience tensions with their Chinese partners, many Western companies are hiring Chinese employees who are then trained in Western business standards by being posted to one of the countries where the company does business. The idea is that it's easier to hire people who already have cultural knowledge and then train them in the ins and outs of the business. Of course, this is a good solution, but it creates a war for talent and leads to higher salary costs. Moreover, this solution does nothing to help establish a reliable working relationship in China. Those who have succeeded in doing this understand how important the role of trusting relationships is in China's dynamically changing business culture.

Myths about gift giving

Western executives have no shortage of advice regarding the gift-giving rituals of Chinese business culture. For example, it is believed that gifts to managers should be more expensive than gifts given to their subordinates.

Meanwhile, more Chinese companies are condemning the practice of gift-giving. As contacts with international partners expand, Chinese business etiquette is changing. The Chinese are paying more and more attention to the professionalism of Western partners and establishing trusting relationships with them.

In this sense, the example of China Data Group (CDG), a rapidly growing company that employs more than 4,000 people, is instructive. CDG, based in Beijing, develops technologies that enable business process outsourcing in information-rich industries such as insurance, credit cards and corporate banking. As CDG intended to expand its business and position itself as an international company, it decided to reduce its reliance on guanxi and focus on brand equity, professionalism and service quality. Expansion plans included entering the markets of Japan and the USA, so CDG began to invite managers with extensive international experience.

To mitigate the conflict between traditional guanxi norms and new international standards, CDG temporarily created two different sales departments: day and evening. The "day team" worked with clients on their sites, discussing projects, making presentations and providing technical support. Its goal was to build customer confidence in the quality and reliability of CDG's services. The "Evening Team" invited clients to dinners and other informal meetings to build personal connections and understanding.

But when one of CDG's senior executives, who worked on the evening team, gave a mobile phone to the head of the company with which CDG eventually signed the largest contract in its history, CDG's top managers differed in their assessment of this action. Some felt that the CDG vice president who negotiated the deal should be rewarded. Others objected, saying such gifts tarnished CDG's reputation and the party team should be disbanded. How did it all end? CDG no longer gives expensive gifts to clients, the “evening team” has been disbanded. Here's a clear example of how Chinese companies are gradually moving away from some traditional cultural norms, bringing their business practices in line with international standards.

About the study

The ideas presented in this article are based on my research, which I have conducted with colleagues over the past 6 years, studying various aspects of trust and cultural psychology in business relationships in China. I began by analyzing the psychological foundations on which managers trust members of their professional networks.

Using a sample of 101 American executives (all in the executive MBA program at Columbia Business School), my colleagues and I studied how executives build relationships with business partners. Our respondents completed network questionnaires, providing us with detailed information about their partners' past experiences and social backgrounds, as well as how they interact with them. Among the key criteria for assessing business relationships were cognitive and affective trust.

In a subsequent study, using the same method, we compared the professional networks of 130 American executives (also participants in an executive MBA program) with the networks of 203 Chinese executives who attended a similar program in China. In both studies, we looked at statistics about how patterns of cognitive and affective trust develop across executive networks and identified systemic patterns and differences using social network analysis techniques. The second wave of information collection consisted of corporate field data. In the first project, we collected data on the basis of trust of Chinese top managers in their foreign partners during communication. The sample consisted of 108 executives of Chinese companies doing business in 12 economically developed provinces on the east coast of China. We asked each of these executives to name two top managers of foreign partner companies: one of Chinese origin, one of non-Chinese origin. During face-to-face interviews, executives answered questions about each of their foreign partners, allowing us to compare how Chinese executives build relationships with Chinese and non-Chinese foreign partners.

To better understand the specifics of business relationships in China, I conducted in-depth interviews with a Beijing business process outsourcing company (CDG) and developed a case study on how its leaders harmonize business and personal relationships in China's rapidly changing economy.

In preparing this article, we also conducted hour-long interviews with 20 American and European executives who had experience working in China to complement our empirical data with living stories. Overall, our research provides sufficient evidence to provide insight into how to most effectively build trust and guanxi in China.

Building trust from the heart across boundaries

Affective trust—or trust from the heart—is critical to effective cross-cultural business relationships. In my research, I have found that the powerful mental habit of cultural awareness (that is, the habit of constantly challenging one's assumptions about another culture) helps in networking because people immediately feel truly understood—rather than stereotyped. . My colleagues and I found that people who were more aware of another culture were more likely to connect and be in tune with members of the other culture more quickly, which contributed to the emergence of affective trust. Leaders who have mastered cultural awareness do four things. They constantly:

Aware of their ideas about another culture;

. check the reality of their ideas - do they help to understand the motivation and predict the behavior of the partner?

. reconsider their ideas if they turn out to be incorrect;

. plan how to use this new information in future interactions.

To master this skill, practice two things. First, take the time to proactively plan your actions before any interactions with Chinese partners. Spend 10 minutes thinking about the following questions:

What are my ideas about Chinese culture? What are the Chinese perceptions of my culture? What do I know? What don't I know?

. How can I use my insights and knowledge in upcoming negotiations? Or are they better used during informal events?

. What problems may arise during negotiations? How can I solve them? What do I need to know to avoid potential misunderstandings?

Secondly, during any interaction, study and observe your Chinese partner. Keep in mind that your ideas about Chinese culture may be incorrect - or inappropriate in a given context. In China, where the difference in the level of economic and social development of different provinces is large, this is especially important. After all, both business norms and customs in different parts of China are less uniform than many non-Chinese believe.

For example, instead of assuming that all Chinese people are concerned about losing face and are therefore extremely reluctant to express their opinions, observe how your partners interact with each other and test your assumptions in practice. If you doubt the correctness of your assumptions, seek advice from a local escort.

Consciously embracing Chinese culture will help your partners feel like you understand them. And this will increase the likelihood of establishing strong business connections.

Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All Rights Reserved

Text: Roy Chua;

Translation from English: Irina Sergeeva

As you know, the success of communicating with a foreigner to some extent depends on regional studies training - knowledge of the history, culture, morals and customs of the corresponding country.

Knowing the national psychological characteristics of various age groups of the Chinese population, our Russian businessman can correctly model the first reaction of a Chinese person with whom he decided to come into contact, and determine possible ways for his further development. In addition, the correctly chosen pretext for making contact is of no small importance.

It is also necessary to take into account that some Chinese consider meeting a foreigner as one of the opportunities to realize their selfish goals, since they believe that the foreigner has significant financial resources. This can also be used for the purpose of establishing and developing acquaintances.

In the process of establishing acquaintance with the Chinese and its further development, knowledge of the customs and rules of their communication acquires special importance. Skillful use of this knowledge in the process of communication will allow you not only to consolidate your acquaintance with a useful Chinese person and study him well, but also to influence him. One of the Chinese proverbs talks about the need to know customs and rules: “When entering a village, learn about local customs, when entering a house, ask for the names of family members.”

Let us dwell only on the most characteristic features of communication in China. Of interest is the manner of communication, which to one degree or another is characteristic of all Chinese.

Communication begins from the moment of meeting. At the same time, the Chinese believe that one must show that he respects the other as an individual. Each of them is obliged to make it known that he considers the other a developed and educated person, even when both understand that this is not really the case.

Greetings are of great importance when entering into contact with a Chinese person. It has a pronounced social connotation, and its form depends, first of all, on the age and social status of the person to whom it is directed: the one who greets the communication partner first is the one who is younger, the greeting is almost always accompanied by a bow (sometimes multiple). The most commonly used forms of greetings are: hello (te) (“ni hao”) (literally: are you good?), good morning (“zaosheng hao”), good evening (“wanshan hao”). One of the most popular is a greeting that literally translates: have you eaten rice, are you full? (“ni chshi fan ma?”). This form of greeting has a special meaning. It is common knowledge that the word "rice" has one of the strongest meanings in traditional Chinese society. The struggle for existence in China sometimes directly depended on its availability. For this reason, this form is largely symbolic: if you “ate rice,” it means there is prosperity in your home and everything is in order with you. At the same time, the use of this greeting in modern China is somewhat limited, and it should be used sparingly, and that, of course, in accordance with the current communicative situation. When meeting good friends, a very emotional expression corresponding to Russian is also often used: “How many years, how many winters?” or “Long time no see!” (“Hendo mei khan zen nile!”).

Obviously, when entering into contact with a Chinese person, appeals play an important role. Since the 40s. XX century In China, calling by surname has become very popular. When addressing a group of people or an audience, they most often say: “Comrades” (“Thongzhimen”). It is characteristic that this address eliminates the need to greet each member of the group separately. In recent years, the address “gentlemen” (“xienshengmen”) has also become less widespread.

When talking with unfamiliar people, the Chinese behave in a peculiar way. They keep the position of their face and body motionless, sit straight, with their back stretched out, do not move at all, only their lips move slightly, and their voice approaches a whisper. Very loud conversation is considered simply unacceptable. Our eyes and eyebrows also tend to move during a conversation, giving the interlocutor additional information about our mood, impressions of the conversation, etc. The Chinese person’s face remains impartial or expresses unctuousness and gratitude - this is a manifestation of his politeness, under which he hides his true feelings and relationships.

The Chinese avoid looking directly into the eyes of their interlocutor. “Only enemies in mortal combat look straight into the eyes,” they believe. For good acquaintances who have gathered for a conversation, glaring at each other is considered indecent to this day.

The Chinese speak calmly and leisurely, and they tend to use beautiful phrases and philosophical sayings. To say “yes” or “no,” the Chinese resort to the most intricate and figurative expressions. To refuse someone something by directly saying “no” is considered rude. Evasiveness is considered a manifestation of intelligence and character. A Chinese will very rarely allow any harsh or offensive remark to be made in a conversation. If he is dissatisfied with something, he will not express it directly, but will tell his interlocutor some fictitious story in which he can find the desired hint. Speaking directly and frankly is not the Chinese style. The Chinese do not like direct questions. Therefore, they prefer to express their thoughts allegorically, using historical and poetic comparisons, various turns of phrase and allusions. Referring to historical novels, the Chinese believe that the authority and experience of their ancestors is indisputable. At the same time, it is believed that a literate Chinese must know three ancient novels: “The Three Kingdoms” (“Sangozhi”), “River Backwaters” (“Shuihu”) and “The Dream in the Red Chamber” (“Honglomen”).

Comparison with someone - the best compliment you will receive from a Chinese person may be that you are like someone. Moreover, sometimes the figure with which you are compared is not always clear to you. Often you have to wonder why or in what respect you were compared to a certain person and how to react to this, from our point of view, dubious compliment. The Chinese themselves feel uneasy if some member of the team is not like anyone else. They rather try to liken him to someone else, and then peace of mind comes.

The Chinese have a rather subtle nature. They are touchy and proud, painfully endure their mistakes, responsive to praise, but do not attach much importance to a set of simple pleasantries uttered in conversation until they are convinced of the sincerity of what is said. They strive to read their partner’s thoughts, to catch the discrepancy with what is being said in the intonations of the voice. Therefore, excessive assertiveness, bias or insincerity in a conversation with a Chinese person can cause a negative reaction in him and even scare him away.

Chinese culture has always emphasized the peculiarities of communication between people. The Chinese are masters of understanding the psychological state of their interlocutor and skillfully using it. At the same time, the Chinese themselves do not consider it possible to let their interlocutor understand their own internal state. They tend to hide their feelings under the guise of a smile or kind words or respectful greetings. The Chinese have learned to control their speech and emotions even at times of great psychological tension. At the same time, it should be noted that under the mask of impartiality and restraint of the Chinese, there is an easily excitable temperament, an impressionable, sensual, vindictive and vindictive nature. Therefore, during a conversation with a Chinese, you need to show maximum restraint, be balanced and tactful.

Organizing the conversation plays an important role in communicating with the Chinese. They, as a rule, willingly talk about the family (primarily about the elderly and the male half of the family). This circumstance is due to the fact that the interests of the family are valued very highly. In addition, the content of the conversation may include issues of national history and culture, Chinese cuisine, and products manufactured in China. The experience of communicating with the Chinese convinces us that such a problem as the annexation of Taiwanese compatriots, Taiwan itself, to China is a topic that all Chinese willingly discuss, since they consider themselves quite competent in this matter. At the same time, when they are on the territory of other countries, they show increased interest in everyday life, sights and other aspects of the social reality that is new to them. And if the Chinese find something of their own in this country or something that has anything to do with China, then this always causes a positive reaction from them. When communicating with people unfamiliar to them, the content of the conversation can be the arrangement of their home, personal affairs, and the likelihood of realizing long-standing plans. However, in this case the conversation is usually of a general nature. The Chinese tell people they know closely about their immediate plans, for example, about the upcoming purchase of a bicycle, a sewing machine, a watch, etc.

The Chinese are incredibly fond of talking about shopping. The question of the price of purchased goods rarely confuses the Chinese. However, it is unlikely that for reasons of “saving his face” he will tell you the real cost. As a rule, the amount is significantly overestimated. At the same time, the price of goods is an integral attribute of dialogue about things to which the Chinese attach exceptional importance. They discuss each purchase many times within the family circle and with people close to them, evaluating each property and all options for its practical use.

Particularly common topics of general discussion include the topic of Chinese literature, history, weather, etc. the development of one or another general topic of conversation, which logically follows from the occasion of communication, must necessarily include text questions and statements that direct the Chinese’s attention to various channels, allowing, however, to maintain a single topic of conversation. For example, when talking about Chinese cuisine, you can clarify the proportions of meat and vegetable ingredients in a particular dish, ask about the differences in cooking in the city and the countryside, in the North and South of China, find out whether there are educational institutions in China that train specialists in Chinese cuisine , speak about the popularity of exotic Chinese dishes abroad, ask about the devices necessary for cooking, about how much and what kind of fuel is used for cooking (fuel saving is the pride of any Chinese), about whether there are conditions for cooking in a modern city apartment dishes of national cuisine, etc. This kind of conversation makes it possible to involve the opposite party in a fairly frank conversation that will provide the necessary diagnosis of the interlocutor’s expected behavior.

Numerous apologies are also noted for their well-known ethnocultural uniqueness. The most popular and frequently used expression is: “Sorry, guilty, unworthy” (“Tsing wen”). This is quite consistent with the ingrained Chinese habit of self-deprecation at every opportunity and is an integral part of the Chinese culture of communication. Among many other forms of apology, the following expressions stand out for their universality: “I regret, I apologize, I express my regret” (“Dui but tsi”) and “Sorry for the trouble, the trouble caused” (“Mafan nile”). In response to these apologies, as a rule, there follows a stereotypical: “Nothing special, it doesn’t matter, it’s not that important” (“Mei guanxi”) or “Not worth gratitude” (“bu xie”). In response to a guest’s apology regarding the inconvenience caused, one can often hear: “Don’t be shy, don’t stand on ceremony” (“Bu khetsi”) or “Nothing, it doesn’t matter, it’s not important” (“Mei guanxi”).

Due to the fact that the spoken Chinese sentence is in most cases simple, emotional means play a significant role in the design of speech, among which interjections play a prominent place. Chinese speech is very rich in them. Interjections according to their meaning can be divided into two fairly independent groups: emotional and dominant. Emotional interjections express the most varied feelings and experiences of the Chinese, his attitude to the speech and actions of the interlocutor, assessment of the situation, etc. and are more numerous. Interjections of the dominant type in the Chinese language are less numerous and primarily express the will or motivation of the speaker. In colloquial (informal) speech, interjections are much more common, especially among rural Chinese. The use of words as pause fillers is also quite widespread among the Chinese. As for onomatopoeia, they are quite rare and, perhaps, not so characteristic of the Chinese. When communicating with the Chinese, you must remember that in conversations they often use not only names, but also nicknames, which are very popular in China. Nicknames usually characterize some negative or other quality of a person (for example, dwarf, short, dumb, fool, monkey, etc.).

The Chinese culture of communication is characterized by the use of non-verbal means of communication. When talking among themselves, the Chinese sometimes use their hands to visually demonstrate the subject of conversation. In particular, with the help of their hands they show the conventional size and shape of the objects under discussion, as well as all conventional operations with them. In the nature of Chinese gestures, it is worth highlighting some differences depending on the specific situation. Thus, in an official setting, the frequency of gestures is reduced and reduced to nothing. Differences in facial expressions and gestures between people from different provinces are obvious. Southerners are more relaxed, they tend to have a rather relaxed manner of communication.

Having examined some verbal and nonverbal signals of the actual behavior of the Chinese, we can talk about their influence on the establishment and development of contact. Speech and non-speech actions (language and accompanying facial expressions and gestures) are not only important material for expressing the emotional states of communication partners, but also a means of transmitting relevant information. The communicative behavior of the Chinese (as well as representatives of some other eastern peoples) is characterized by quite pronounced ceremony, restraint, secrecy, turning into slowness, and the presence of a large number of stable mandatory colloquial and procedural “politeness stamps.” At the same time, a distinctive feature of the Eastern communication scheme is the mutual gaze of communication partners in the process of interpersonal communication. Verbal and non-verbal communication with the Chinese is also characterized by the fact that it requires a certain patience due to the presence in their ethnic psychology of such qualities as reluctance to make decisions on their own, lack of inclination to take risks, and the habit ingrained in their minds of repeating the same thing several times, often leave the question unanswered, etc. Consequently, knowledge of the behavioral characteristics of the Chinese, determined by the uniqueness of the ethnocultural environment, and their adequate interpretation help to increase the diagnosis of negative aspects in maintaining interpersonal relationships.

The Chinese love jokes and laugh a lot. A Chinese proverb says: “Anger makes you old, laughter makes you young.” At the same time, the Chinese often use proverbs, sayings, and allegories, which demonstrate such traits of the Chinese character as cheerfulness and wit. Knowledge and use of proverbs and sayings will not only decorate the speech of our compatriot, but will also help strengthen his authority in the eyes of the Chinese.

In their interlocutor, the Chinese value not only the manner of conversation, but also his intelligence, wisdom, and experience, which they place above physical abilities. An interlocutor who knows the history and literature of China well is respected.

Knowledge of the national psychological characteristics listed above will help the Russian partner establish and develop acquaintances with the Chinese. He must look for such forms of personal communication that would allow him to reveal the true feelings and intentions of the Chinese, to determine the degree of sincerity of his relationship towards him. In addition, correctly selected forms and methods of communication make it possible to influence the Chinese in order to successfully solve business problems.

It is necessary to take into account that the Chinese perceive primarily the form, and not the content of any phenomenon (addresses, phrases, etc.). Thus, the method of historical analogies, designed to appeal to the value of the past in the minds of the Chinese population, was present in almost all ideological and political campaigns, the periodic holding of which was caused by various reasons for the internal political situation in the PRC. At the same time, the main commandment of Maoist propaganda was the impact of form, not content, which took into account, firstly, the value of form as such for the Chinese and, secondly, the fact that the form can be endowed with psychologically consonant characteristics, thanks to which the content hidden behind it will be taken for granted.

In its practical activities, the Russian partner can use similar methods of influencing the Chinese, since they most fully take into account their national psychological characteristics.

Below is brief information about some features of the national character and linguistic thinking of the Chinese partners, communication with which has always presented a certain difficulty for the Russian side.

1. For a Chinese, any official contact with a European is, first of all, a meeting with another world, it is always a duel from which he must emerge victorious to the cheers of his compatriots. If we, Russians, ask the leader of the Russian side during negotiations about the results achieved, then our question usually does not have a “nationally civilized” connotation, and for us the Chinese are the same partner as the British, Indians, etc. The Chinese are a different matter . They are interested in the result of communication and, in this regard, what the Chinese side looked like against the background of the Western “barbarians,” and how far they were able to impose their “preparations” on the opposite side. This approach is rooted in the very depths of the Chinese psyche and is present in a hidden form in any negotiations. Hence the psychological readiness to put “pressure” on a partner, serious preparation for negotiations, and attention to all formal details.

2. The behavior of the Chinese in any life situation is largely determined by stencils, which go back to the commandments of ancient philosophers and form the basis of education to this day. This may seem like an anachronism that does not help, but hinders decision-making in specific circumstances. However, it is enough to remember our good soldier, who was thoroughly drilled into the provisions of the Guard Service Charter and who, in an extreme situation, automatically acts according to the learned “scenario” and acts, as a rule, correctly. An analogy is appropriate to draw on the actions of the Chinese during the negotiations. From the book “The Art of War”, revered by every Chinese, by the ancient philosopher Sun Tzu, a whole series of practical advice follows, such as: “find the enemy’s weak point and strike, the enemy has fallen - finish off”, etc. Here it can be argued that in any book devoted to war, there are similar recommendations (just remember “The Art of Victory” by A. Suvorov). However, for us such books and such commandments are nothing more than facts of history, distant or close, while for the Chinese it is the state of his consciousness, his attitude and behavior. Naturally, such traditional upbringing is easily supported by all sorts of modern instructions and instructions, which in some cases makes the Chinese more confident in his behavior than his Western partner.

3. For thousands of years, the Chinese have lived under a strictly centralized state, which has taught them top-down discipline and precise execution of a narrowly defined task. As a rule, all negotiations conducted by the Chinese with the Russian side, regardless of the rank and scale of the negotiations, are “conducted” from one console. An analysis of the behavior of the Chinese during negotiations and private confidential conversations with them lead to the idea that there are some centralized instructions on how to trade with Russia and how to impose their own conditions on it (as a rule, not beneficial to Russia).

4. It is known that the Chinese are taught to strictly control their emotions from childhood. This is typical for the entire East, but for China in particular. Direct display of feelings, especially in front of foreigners, is considered absolutely unacceptable. In this regard, of great interest are the studies of the Hong Kong authors “The Art of War” by Sun Tzu and “The Art of Management in Business” (1994), which has been formed over thousands of years - it gives the Chinese certain advantages during negotiations - a smile mask allows the Chinese to avoid an unexpected direct question, to translate conversation on another topic, thus gaining time, and returning to the question posed with a thought-out answer. At the same time, the Chinese always tenaciously monitor the facial expression of the interlocutor and constantly analyze the partner’s emotional reaction to his remarks and questions. In the Chinese tradition, it is to conduct a conversation in such a way as to emotionally “sway” the interlocutor, push him to more or less direct expression of feelings and through this understand the true intention of the partner.

5. Almost all experts on China note such an “innate” trait of the Chinese as subconscious egocentrism, which at the everyday level can be formulated as follows: “it’s so convenient and beneficial for me.”

Is it convenient and beneficial for others? The average Chinese usually doesn’t think about it. According to the “laws” of egocentrism, Chinese society has lived for thousands of years, and no amount of education can eradicate what is inherent in the entire way of life, although the corresponding verbal rhetoric (“taking into account your wishes...”, “we understand your problems...”) has been worked out quite well. Egocentrism is also characteristic of foreign policy, which is not least due to the arrogant idea of the ancient Chinese about the “middle” position of their state.

6. The Chinese are characterized by so-called “strategic” thinking and behavior (not an official term) - methodicality, determination and perseverance in realizing a long-term goal, regardless of the effort expended. Among the Chinese, behavioral stereotypes are formed under the strong influence of folk tales, which reflect the deep properties of the national psyche. One of these parables, and one of the most popular, tells specifically about the fanatical perseverance of a man who set a “super task” for his clan - to move a mountain (“Old Man Yu moves a mountain”), the solution of which required the daily efforts of more than one generation.

7. Since ancient times, the Chinese have worshiped strength. The transition from a subservient attitude (“I have a strong partner in front of me”) to a harsh dictate (“the partner has weakened”) usually took place quickly and cynically (cynically from the position of Western morality).

These are some of the psychological characteristics underlying the behavior of the Chinese. Now a few comments of a more specific nature.

The strength of the Chinese is their good knowledge of their counterparts. Unlike the Russian side, the Chinese side clearly knows the names of all members of the Russian delegation, the names of their positions, and often their service record. The situation is similar with the subject of negotiations. Russian representatives may know the essence of the issue much more deeply, but often do not have the so-called “background knowledge” on the subject.

Another feature of the “Chinese approach” is the desire to impose a large number of questions and put their partners in the position of being on the defensive, answering questions that very often are not directly related to the subject of negotiations, but create a psychologically unfavorable situation for the opposite side.

The Chinese cannot be denied the ability to quickly find the “pain points” of their interlocutor and derive tangible benefits from this. Having realized the partner’s dependence on one or another circumstance, the Chinese side is able to quickly adjust its line of behavior and base its entire further game on influencing these “pain points.” There is no need to expect generosity here. The Chinese are good at using any illogicalities in their partner’s position. In general, this is one of the main rules that the Chinese strictly follow during negotiations - to find inconsistencies in what a foreigner says with the actual state of affairs.

The traditional “Asian” method of doing business is to extract maximum information by breaking down a general problem into many small ones. It is known that the closer to a specific private issue, the less “politics”, control, “secrets”. During negotiations, the Chinese often strive to create a larger number of working groups and subgroups in order to establish direct contact between specialists and routinely ask a lot of technical “harmless” questions, which are then summed up from all groups, and as a result, a common “picture” is created, which impossible to obtain through normal negotiations.

Very often, the Chinese skillfully use official receptions, banquets, dinners and other events where there is a reason to drink to the success of cooperation, to obtain additional information or to clarify existing assumptions. In these cases, the task of the Chinese is to be persistent and bring the guest “to the required condition”; The Chinese side may offer a “parity” principle (“I have a full glass and you have a full glass”), which our compatriots usually accept with pleasure and without a second thought (“we are stronger than the Chinese”). However, after a certain moment (when the “client has matured”), a Chinese man joins the conversation, who only imitated drinking alcohol and whose task is precisely to extract maximum information from the guest’s facial expressions, fragments of phrases, and his emotional reaction to certain questions . In the estimate of entertainment expenses, alcohol is always given the green light.

The Chinese pay very serious attention to the translation and, more broadly, language aspect of negotiations. It is considered unacceptable for the Chinese side to go on a foreign trip without their own translator, and not one brought in from another organization, but their own, a full-time one, specializing in the specific topic of these negotiations. The question here is not so much a matter of distrust of the translator from the opposite side, but rather a sober understanding of the objective complexities of interlingual communication. In addition, Chinese translators are the “eyes and ears” of the relevant services. As a rule, each translator has his own task and his own “questionnaire”. There are cases when a Chinese translator seems to correct the expressed thought, which “does not fit” into the instructions given. As for the Russian side, there is often a facile idea of the opportunities that open up provided that you carefully prepare your own language and prepare your translator to work as part of a specific delegation.

The issue of the quality of translation of contract articles requires special discussion. It is known that the Chinese carefully analyze our version of translations into Chinese, trying to find any manifestations of ambiguity in order to later use these logical flaws for their own selfish purposes. One cannot expect generosity from Chinese partners here.

Generally speaking, official Chinese delegations (precisely official ones) give the impression of a well-coordinated team, correct in behavior, psychologically prepared to achieve the task, with a sense of their strength and internal superiority. If we add to this the Chinese attention to the formal side of the matter (accuracy in time, knowledge of the protocol, a fairly high level of entertainment expenses), then you get a complete picture of a worthy and complex partner.

How can you adjust your line of behavior taking into account the national psychological characteristics of the Chinese?

1. An analysis of the behavior of the Chinese in the Russian market leads to the idea that the starting point for them is the thesis: the “big brother” is seriously ill - a rare chance to strengthen their position at his expense. The total collection of economic (and other) information allows one to judge the financial situation of a particular enterprise and “twist their arms.” In this regard, the arms trade is an interesting phenomenon: on the one hand, Russian military-industrial complex enterprises are in dire need of financial injections, which pushes them to humiliatingly expect corresponding orders from the Chinese side, for which they are ready to make significant concessions; on the other hand, in the foreseeable future China can only obtain modern weapons and technology from Russia. The question arises: who needs whom more? It seems that Russia's position here looks preferable. The problem is the need for a psychological change. As for the Russian side, in many documents, even in government orders on the sale of this or that weapon, “defeatist” (or clearly non-offensive) notes can be discerned through the lines. It seems that in the entire scheme of contract preparation, negotiations, etc., there should be a clear offensive line.

2. Many participants from the Russian side consider China a natural ally of Russia - taking into account the common historical destinies, sympathy for the successes of Chinese socialism, taking into account the decreasing role of Russia in the world. As a result of such sentiments, individual “negotiators” may lose their “fighting spirit” and make partial concessions (not necessarily on the issue of prices). At the same time, the strict pragmatic orientation of China's policy is completely obvious. Moreover, at a certain stage, China from a “strategic partner” can overnight turn into a “strategic adversary” - just remember the geopolitical position of the two countries and the demographic factor. The Russian side’s line of conduct should be very correct, but without any “fraternization” sentiments.

3. Taking into account the fact that the Chinese hobby is searching for any inconsistencies in the partner’s statements, it seems advisable to conduct specific “command staff exercises” at the stage of preparation and negotiations. During such control operations, one side (the Chinese) must question all the main positions of the Russian side, that is, it is necessary, if possible, to think through all the tricky questions that the Chinese may ask during negotiations.

Along with the search for serious arguments in defense of its position, the Russian side should, as the Chinese do, make it a rule to carefully analyze the statements of the opposite side from the point of view of compliance with their logic, identify “stretches” in logical transitions and actively use them to their advantage. The experience of negotiations shows that serious “trump cards” can be found along this path. The main thing here is to give your partner the opportunity to speak out, take your time with the discussion, ask a sufficient number of clarifying questions, gain time and think over your reaction to the stated position of the Chinese side during the break.

In general, the most unpromising way in negotiations is to get involved in the debate “half-turn”, instantly revealing your “home preparations”. Directly expressed agreement, as well as disagreement, is highly undesirable. It has been noticed that emphasized calm and dignity often infuriates the Chinese, which under certain circumstances can be very useful for the Russian side.

4. Particular attention should be paid to analyzing the questions that the Chinese ask ordinary negotiators. Usually these issues are beyond the sight of the head of the Russian side. At the same time, “collecting” such questions and generalization can shed additional light on the true intentions of the Chinese partner.

5. It is known that to achieve good results in any negotiations, a respectful attitude towards your partner is required. This is especially true for the Chinese. A well-placed compliment and praise play a much larger role in negotiations with the Chinese than when communicating with European partners. A proven way to the heart of a Chinese person is knowledge of Chinese culture and traditions. If your French partner perceives your example from French literature as a beautiful figure of speech, then for the Chinese your short excursion into Chinese history or, by the way, a Chinese proverb said will create a more friendly atmosphere.

A special conversation requires the linguistic behavior of the negotiators, the ability to formulate their speech (monologue and dialogic) in such a way that it is completely understandable to the partner and gives him a feeling of additional psychological comfort.

When communicating with speakers of Indo-European languages, we a priori proceed from the fact that: a) the logic of constructing a phrase in a given specific pair of languages is basically the same; b) the system of figurative means is largely the same; c) Russian-speaking and foreign-language cultures have long traditions of interaction. As for such elements of linguistic behavior as repetitions, rhetorical questions, comparisons, phrase length, etc., they are perceived as elements of speech culture in general, without reference to a specific language. The long traditions of interaction between Indo-European linguistic cultures and the systemic commonality of the corresponding languages have taught us the idea that the main thing is a well-delivered Russian phrase, and as for its sound in a foreign language, this is solely a matter for the translator, and with a good translator there will be no loss of meaning or distortion must. This is a well-established and generally correct idea. But only until we interacted with speakers of some languages of the Far Eastern region, who have a number of features in terms of the sequence of presentation of thoughts, and in terms of the length of phrases, and in terms of the frequency of use of one or another means of expression, etc. Chinese is one of these languages. If you do not adapt your speech, do not rely on “grammar for the listener,” then logical accents may be erased, and the aesthetics of the phrase may not be revealed, and even the most experienced translator will not be able to ensure the adequacy of the translation.

It seems that such negative aspects of the linguistic behavior of the Russian side, which the leader is not even aware of, can and should be minimized as much as possible.

We will try to show some features of the Chinese language that form and correspond to the features of the linguistic thinking of the Chinese.

1. Due to the fact that in the Chinese language there is a certain deficiency of the actual grammatical means (there are no endings, the expression of gender and number is optional, there is no grammatical agreement, etc.), the overall coherence of the text is based primarily on such a sequence of facts and events , which should not happen in real life. Therefore, it is advisable to construct a Russian phrase in approximately the same way.

2. The Chinese language describes a certain situation in a more detailed way than Russian; in other words, Chinese texts usually contain more simple and short sentences. Let's explain with an example. In Russian, the sentence “The barking dog woke up the child” sounds quite normal. In Chinese, this rather complex content will be conveyed by two successive events: “The dog barked (first event), and the child woke up (second event).” Of course, an expression like: why know such linguistic subtleties is appropriate here, this is entirely up to the translator. For a specific example, the objection is completely appropriate. But if the length of the Russian sentence and, accordingly, the number of events “condensed” in it are significant, this will cause great translation problems in conditions of time shortage and difficult perception by the Chinese side of the general meaning of what was said. As a result, failures in communication and a negative psychological background are possible.

3. As you know, in the Chinese language there are no attributive clauses like Russian with the conjunction word “which”. Phrases with the word “which” and, in general, attributive phrases should be treated with particular care. In Russian we can say: “The text of the protocol, which was agreed upon yesterday by the heads of the working groups at their meetings, which were held in an orderly manner and on time, and which reflects the position of the Russian side to the maximum extent, will be fully ready for signing by the end of the day.” The phrase is far from ideal in terms of style, but it is quite typical and is perceived by a Russian-speaking listener without much difficulty. However, it is very difficult to translate such a phrase smoothly - taking into account the fact that this phrase is followed without a pause by two or three more similar sentences - and the problem here, as in the example above, is not only and not so much the qualifications of the translator. The fact is that in Chinese the definition always comes before the word being defined, and the longer the definition, the more difficult it is for the listener to determine which word it defines. This also causes internal irritation and discomfort in listeners.

4. You need to know that in the Chinese language the degree of opposition between oral and written speech is much greater than in Russian (meaning the syntactic aspect). This must be taken into account in the process of oral communication when drawing up the most important documents, since the Chinese do not miss the opportunity to use this contradiction to achieve their own goals.

5. A significant role in achieving a positive communicative effect in the Chinese language is played by repetitions and interrogative sentences that draw attention to a particular problem. When working with the Chinese, there is no need to be afraid of repetitions and tautology. Repetitions and underlining create a favorable background for the coherent presentation of your thoughts.

6. Anyone who is somehow connected with China knows how much a good joke is valued in this country. Russians are also big fans of jokes, and it is rare for Russian-Chinese negotiations to take place in a completely dry atmosphere. But the problem here is that the jokes of the two peoples are rooted in completely different cultural and civilizational traditions. You can joke only if you are absolutely sure that the joke will “work” and will not cause puzzled looks or strained smiles. For example, jokes that are so beloved by the Russian public, as a rule, do not find the proper response in the souls of the Chinese. The Chinese react without understanding (and sometimes with internal irritation) to jokes on sexual topics or topics of adultery. Jokes like: “Why was Comrade Wang late? He probably went to the left yesterday, because there are a lot of beautiful girls in Novosibirsk” - they seem wild and devoid of wit to the Chinese.

7. The Chinese language is in many ways more specific than Russian. We can say: “Who will get the laurels of the winner?” meaning “Who will be the winner?” or “We must not put the cart before the horse” to mean “We must act consistently, according to the logic of cause and effect,” etc. In other words, we can be less specific and more specific. For the Chinese language, more specific forms of expressing thoughts are preferable. Taking this feature into account when communicating with Chinese partners allows you to save valuable time (very often a short remark with a figurative meaning thrown by the Russian side forces the Chinese translator to ask again, and the Russian to indulge in long-winded explanations).

Based on the above, first of all it must be borne in mind that the Russian partner must have good knowledge of the history and traditions of China. This knowledge is needed in order to use their cognitive interest when establishing contacts with the Chinese, to influence their emotions and feelings, to be able to arouse their interest in oneself, to make a pleasant impression, to choose the right reason for contact or a good topic for conversation, the right line their behavior at future meetings.

The desire of the Han people to make contact with strangers creates generally favorable opportunities for an enterprising person to establish a circle of useful acquaintances. It is probably not difficult to gain the favor of a Chinese person if you speak well and respectfully about his homeland, emphasize your admiration for the history, culture and successes of China, and show your knowledge in this matter. As a result of communication, the Chinese should be left with a pleasant feeling, he should be convinced that he is communicating with a worthy person. At the same time, it is most seriously necessary to take into account that when communicating and working with the Chinese, any unflattering assessment of China and its people causes misunderstanding or a hostile reaction.

It is important to know that the Chinese are very proud and touchy. For most of them, a sense of national pride is intertwined with a sense of personal dignity, with a strong belief in the value of their personality. An offended Chinese becomes vindictive; he will not forgive the insult and will patiently wait for an opportunity to take revenge on the offender.

It is characteristic that the Chinese perceive the insult with equanimity. Sometimes we may not even notice that we have offended him, and at the same time he will not show his feelings in any way. The Russian partner must always be extremely tactful and attentive in dealing with the Chinese.

When you have personal contact with the Chinese in the process of studying them, the question of mutual trust inevitably arises. This aspect, in principle, is universal, but in relations with the Chinese it becomes especially acute due to a certain wariness towards Eastern peoples that is deeply rooted in our consciousness.

During contacts with the Chinese, you often get the feeling that they are being dark, behaving insincerely, or not telling something. This feeling arises in you as a result of the fact that the Chinese are characterized by this manner of behavior due to the deep differences in the political, economic and social spheres between our countries. At the same time, it is necessary to understand that the Chinese enter into contact, and even more so into trusting relationships, very carefully and slowly, moreover, distrust of foreigners is part of their historical heritage.

At the same time, it must be taken into account that the sincerity and frankness of the Han people are significantly different from ours. They even have a saying: “Whenever we open our mouths, lies come out of our lips.” Sometimes, as difficult as it is for a Chinese to tell the truth, it is just as difficult to believe it if it is expressed by someone.

At the stage of establishing and consolidating acquaintances with Chinese, our compatriot’s task is to turn the Chinese’s initial desire to meet with him, sometimes based on not yet fully realized curiosity, on affected feelings, into an active, motivated desire to continue acquaintance. But you must be prepared for the fact that a lot of time passes between the preliminary oral agreement and the final decision in the form of a written contract, for example, on business cooperation, during which the Chinese position may change several times. In this situation, it is necessary to show maximum patience. It should be borne in mind that when doing business with the Chinese it is impossible to act according to a pre-conceived plan. We must assume that they will adjust already agreed upon decisions on the fly and unexpectedly abandon any promises. This is a consequence of the characteristics of the Chinese, their psychology, and attitude towards foreigners.

Psychological aspects of negotiations with the Chinese.

The place of negotiations is China. The Chinese like to set the meeting place in their office or in meeting rooms of various public places (hotels, restaurants, business centers). If the Chinese have priority in choosing and assigning a place for negotiations, it would be appropriate to ask the other party where exactly they are scheduling a meeting, what kind of place it is, and what the full program for the negotiations will be. Typically, Chinese companies have a tradition of combining negotiations with subsequent refreshments. It is not always convenient to refuse this, but when it comes as a complete surprise to you, it will not be easy for you to refuse and, most importantly, to be understood by the Chinese. Eating in China is part of the negotiation process; refusal of food is sometimes perceived as an insult or an insult (especially if lunch or dinner has already been ordered in advance). However, it should be taken into account that the lack of advance notice of a planned joint meal on the part of the Chinese is also a gross violation of etiquette, including Chinese. Almost always, these types of events are discussed with foreign guests in advance.

If there is no clear delineation of responsibilities for choosing a place for negotiations between the parties and you do not feel constrained in choosing such a place, it is better to choose something that is most suitable for you in terms of the style and habits of a European person. Usually, if the place of negotiations is appointed by the Russian side, this evokes respect from the Chinese partner. Especially if this place is chosen in a purely Western business style (special meeting rooms at hotels, specialized business centers for foreigners, Russian institutions abroad). The further course of the negotiations and the attitude of the Chinese side largely depend on the meeting place during the first acquaintance, if the Chinese understand that you paid a lot of money for renting an apartment, or when the meeting takes place on the territory of diplomatic institutions. This obliges the Chinese to be serious, gives you additional trump cards in terms of psychological influence on your partner and facilitates the negotiation process in the direction you want.

The place of negotiations is Russia. When planning a meeting with the Chinese on your territory, you should under no circumstances accept invitations from your Chinese partner (if the initiative comes from him) without first stipulating the place of negotiations. It is likely that the Chinese are simply inviting you to their hotel room for “sofa talks.” Agreements reached during such “get-togethers” usually end in nothing. The Chinese who come to Russia are determined to find out your level of wealth, assess the degree of your interest in the transaction, and will do this based on the practical steps you take in relation to them. Appointing a “worthy” place for negotiations is half the success.

If you do not have a well-equipped meeting room in your office, it is better to negotiate on neutral territory when you first meet. Transferring subsequent negotiations to your office will pleasantly surprise your Chinese partners and give you an extra plus. Don’t be afraid to be caught “showing off.” Being probably the biggest poseurs in the world, the Chinese rarely notice this vice in Europeans, unless, of course, they go too far. When demonstrating your financial status and wealth, it is important to maintain a certain middle ground, in no way showing that the surprise and admiration of the Chinese (who may be many times richer than you) flatters your pride and that this is exactly the effect you were trying to achieve with this entire demonstration. Modesty has the greatest effect, especially when it is natural.