Remove bugs while lying on moss that has absorbed all the Carpathian moisture? What kind of romance and passion is here, many will ask. Of course, you can flatly tell everyone that you are engaged in “entomological macro photography,” but will the average person who just wants to know how photographers work with insects understand you? It seems to us that the time has finally come to talk about this difficult subtype of photography. But first, let's talk a little about photography in general.

For realism

Photographers learn quickly these days. Especially with digital, when you have the opportunity to control your mistakes in real time. Now a young photographer has every chance to leapfrog through the phase of growing up in photography, which took two to three times more effort and hours during his film years. The genre that we will talk about today belongs to the most complex areas of modern photography, both technically and artistically. Considering the topic of macro photography of insects, we decided not to include images that were overloaded with computer processing, or with an overt bias towards “art modernism”. If we really, through photography, study the tiny inhabitants of the grassy above-ground microcosm, if we really passionately capture a frame with a flying dragonfly or a crawling caterpillar, then let's do it in its purest form. There is a photographer, there is a camera and there is an insect. Let's concentrate on describing only these three components and weed out all unnecessary things. Naturally, we will pay increased attention to the camera as a general element of the technical side of macro photography.

The famous German photographer Karl Blossfeldt was the first to use macro photography. He photographed plant details in the studio, achieving 30x magnification using a camera he designed himself. His works are extremely realistic, but at the same time, he departed from the established canons of photography of his time, because he imposed on the public a new way of looking at the world through the lens of a camera. For this, many considered him an abstract freethinker and could not appreciate in him a creator who rose a step above the rest. Now, when photography has long served many of the needs of civilization, and cameras can photograph both hydrogen atoms and superclusters of galaxies at distances of billions of light years, we can quite consciously talk about the value of images. It is also worth talking about this because now we are often faced with the era of imposing pseudo-photographs on us, created on a computer from various scraps of various images, subjectively thought out into a composition.

So, if the image is a photograph and reflects an objective cross-section of the event, and is not a collaged interpretation, it is already worthy of attention as a documentary fact of what happened. But is this enough for insect macro photography? No, because, as elsewhere, in photography one should look for a creative principle that subconsciously attracts the viewer to itself.

The aesthetic fundamental principle of realistic macro photography should be the isolation of images, their laconicism. Trying to make the viewer fall in love with a caterpillar that has been disgusting to him since childhood is pointless. A person’s banal disgust and rejection of a caterpillar or other similar creatures may be rooted in the sphere of the unconscious. There is only one way out - the most reliable image of a bug, exceptionally detailed, from an unobtrusive angle, emphasizing the beauty of shapes and patterns. Whatever one may say, the photographer opening it should not be afraid to crouch to the ground and look where the space is crowded with sources of hostility. And in order to not only dare to look, but also to subjugate this space to create beautiful portraits of moths, mantises, caterpillars, weevils, scarabs and spiders, you just need to love this thing. We have only touched on part of the topic of macro photography ethics. In addition to developing the right attitude and choosing the direction for developing your own macro-creativity, there are thousands of applied nuances. Wet feet trying to peck their nose into a puddle, long-focus macro lenses, the wind throwing a blade of grass with a butterfly in different directions, scanty lighting on the lower tiers of vegetation, etc. But this is a necessary working routine on the path of any creator to a masterpiece. Without a routine, it is impossible to come to God; without a long-term routine, moments of revelation from meeting the beautiful are impossible.

Macrobirth

Blossfeldt created his photoherbarium over 30 years. Methodically, day after day, he collected stems and flowers of wild plants from the field and then photographed them against a neutral cardboard background, mostly illuminated by diffuse natural light. Karl used a large-format camera of his own design with bellows that allowed him to reduce the focusing distance and achieve a phenomenal magnification for that time - from 4 to 30 times relative to the original. Of course, photographing dead plants in the studio and photographing spider beetles in their natural habitat are not the same thing. But still, adherents of modern macro photography must definitely find a place for it in their story about the history of the progressive development of the genre. Unfortunately, the technical details of Blossfeldt's work are not known to us. But we are happy to tell you about the birth of the first prototype of a consumer macro lens. Until the 50s of the last century, the term macrophotography smoothly flowed into the definition of microphotography. The latter includes film/photography of objects and their details using an electron or optical microscope with a magnification of 20-3500 times. That is, microphotography is under the jurisdiction of science. Previously, macro photography served exclusively scientific purposes. This is evidenced by its official definition: shooting objects, their elements and structures on a scale from 1:10 to 15:1 using special or ordinary lenses. But the fact of the matter is that for ordinary lenses, 15x magnification is fantastic. Even today, Canon's flagship consumer macro lens, the $1,300 MP-E 65mm f/2.8 1-5X Macro Photo lens, only achieves 5x magnification. As for the other extreme, in the West, for example, photographic images of objects on a scale from 1:10 (10th part of natural size) to 1:1 are not considered macro photography at all, using the term close-up - literally “close-up”. By the way, for that matter, it is somewhat paradoxical to use the prefix “macro”, which means something large sizes to the type of shooting tiny objects.

The very first publicly available true macro lens was born in Japan. Nikon has distinguished itself, or rather, the famous professor Koan, collaborating with it. But the reason for the creation of such a lens was not the urgent need of field entomologists. Immediately after World War II, the United States introduced a high-tech system of photo archiving of historically significant documents in Japan. True, its main component, the optical system, did not have sufficient resolution. Sufficient to clearly reproduce the characters of the writing system borrowed from the Chinese. And now, after lengthy laboratory work, Professor Koana presents to the public a sample of Ichio Higuchi’s 70-page novella, reshot using the new Micro Nikkor 50 mm F/3.5. It was possible to see every stick, diagonal and stroke of hieroglyphs without any problems. Based on this lens, in 1956 specialists developed the Micro Nikkor for S-type cameras, and in 1961 the world saw its amateur version with a focal length of 55 mm, intended for Nikon F. Naturally, the development of macro photography was not only stimulated by one company. In general, in the assortment of every serious manufacturer of photographic equipment there are at least a hundred different accessories designed to make life easier for those who like to depict small things on a large scale.

Theory close up

To simplify the concept of the topic, let's start from the definition that a macro photograph should be considered a life-size image of an object on the plane of the sensor or film, i.e., on a scale of 1:1. Enlargement to such proportions is purely an optical characteristic. That is, in the case of a 35 mm format, the lens should be able to focus on an area of 24×36 mm, and an object of this size should fill it all. By replacing the same “glass” with a digital SLR camera with a sensor area of 15×22.5 mm, we get an object with the same proportions, only cropped at the edges. If it were entirely contained within a sensor area smaller than a 35mm frame, it would no longer be possible to talk about a 1:1 scale. Do not confuse the ability of a lens to focus at close distances, reproducing a life-size subject, with the magnification factor provided by telephoto lenses. The latter bring distant objects closer due to their large focal length, but do not necessarily depict them at a 1:1 scale. The optical system of a camera, for example, an amateur digital one, may have a macro mode and a minimum focusing distance of only a few centimeters. And still not provide an increase to natural sizes. It seems that even in school physics they taught: if the distances from the object to the lens and from the lens to the image are equal to two of its focal lengths, then the dimensions of the image and the object are also equal. It is not difficult to come to the conclusion that higher magnification can be achieved by positioning the lens away from the film/sensor plane. Most standard lenses consist of several lenses of an asymmetrical design, and only produce sharp images when the distance between them and the film/matrix is significantly less than the distance from the front lens to the subject. Or, in extreme cases, equal to the focal length, and the object is at infinity. In principle, any lens focuses by moving its optical elements further or closer to the sensor plane. In practice, one of the fundamental principles of a macro lens design is expressed in providing a greater range of mobility of its optical elements. If you move the lenses further from the sensor plane, the lens will focus on objects closer to it. And vice versa. So the first case is the basis for the layout of the macro lens elements. As a rule, conventional macro lenses for narrow format SLR cameras allow you to create images at a 1:1 scale. If someone wants to photograph a bug that is too small, they will have to use additional devices to achieve a larger scale. That is, in accordance with the above reasoning, for example, moving the optical center of the lens away from the plane of the film/matrix. More on this a little later.

A little more theory

Question: is it still possible to take real macro photographs using a compact digital camera? Answer: you can. For example, one of the leading macrophotographers in Europe, Pole Mark Plonski, started with this. First he photographed the Canon PowerShot G1, then the G3. True, I immediately realized that in order to get not just “close-up” shots, but something similar to a real macro, additional devices would be needed. After all, it is almost impossible to use the macro mode of compact models. Removing a bug from a distance of 3-4 cm is almost utopian. He simply won’t let you get that close to him. Focusing in the “tele” position of the lens on Mark’s camera was only possible from a distance of several tens of centimeters. It was not worth even dreaming of an increase that would allow the frame to be classified at least in the “close-up” category. Therefore, the photographer used diopter attachments (macro lenses) that screw onto the lens. These are single lenses that serve as a kind of magnifying filter. They allow you to reduce the distance to the subject being photographed - shorten the focusing distance, which results in an increase in scale. Let's stop to understand two key terms in macro photography. First of all, the minimum focusing distance. This is the distance from the film/sensor plane to the subject, closer than which focusing is impossible. And this is not the same as working distance. It denotes the length of the segment from the subject to the front lens of the lens and, obviously, depends on the focal length of the lens itself and its physical length. A working distance that is too short is undesirable, since again practical difficulties may arise with shooting close to the insect. And it’s not easy to illuminate it in such conditions - only side lighting is effective. For reference: a 100 mm Canon macro lens at a 1:1 scale will provide a working distance of approximately 10 cm, while a 180 mm lens will be more than 20 cm. But let’s return to Mark Plonsky’s digital-compact macro solution. To achieve maximum magnification from the G3, he screwed several diopter attachments with an optical power from +1 to +10 onto the lens using a special adapter made by Lensmate. The rule is that the attachment with maximum optical power should be placed closer to the lens. Mark brought its value to +27 at a time. True, this was done for the sake of experimentation. There was no need to talk about the acceptable quality of such images. By the way, you can calculate the overall magnification effect of diopter filters using the following formula: f/(1000/d), where f is the maximum focal length of the lens, d is the value in diopters of the attachment. That is, Mark “dabbled” with almost 4x magnification! It's a lot? It would really be a lot if his G3 initially gave a 1:1 scale. It should be noted that of all the additional accessories whose purpose is to maximize the effective magnification of the lens, diopter macro attachments have the greatest Negative influence on image quality. There are attachments consisting of two paired optical elements. They are more expensive, but also usually undergo more thorough optical correction.

Sharp Depths

DOF in macro photography is a special topic. As the scale increases, it invariably decreases. It is more convenient to think of depth of field in macro photography as a small, clearly depicted passage, the distance from the nearest to the farthest sharp point. As an artistic technique, it certainly does not lose its power when shooting at a 1:1 scale. But as you approach the object at critically short distances, it becomes difficult to control. In addition to the scale, the depth of field depends on the size of the so-called circle of dispersion - a distorted image of the point formed by a particular optical system due to its defocusing of a beam of rays. It has been established that even the most perfect lens cannot focus the rays perfectly. Of course, up to certain limits there is no difference between a perfectly sharp image and a slightly out-of-focus image. Through experiments and calculations, optical specialists established the following limits for the permissible blur spot diameter: for 35 mm film - 0.033 mm, for medium format - 0.05 mm. How is it related to depth of field? The connection follows from the following definition: depth of field is the range of distances on the optical axis in object space, within which the size of the blur spot does not exceed the permissible value.

We know that the larger the aperture value, the greater the proportion of objects within the field of focus. This works in landscape photography, but when focusing at close range the depth of field is reduced to millimeters. Let's say if you're shooting at a 1:10 scale, which corresponds to a photographic area of 24x36 cm for a 35mm format, and 23x15 cm for a Nikon-DX format sensor, then the range of depth of field will vary from 4 cm at f/5.6 up to 15 cm at f/22. But a 1:1 scale will already be marked by approximately the following depth of field values: about a millimeter at f/5.6 and no more than three at f/22 (if we take the circle of dispersion equal to 0.033). So what should we do? Close the aperture to the limit? Not a solution, since after f/11 the diffraction effect begins to appear. This is a phenomenon observed when light propagates past the sharp edges of opaque or transparent bodies - in this case, the aperture opening, which is accompanied by the deviation of its rays from the laws of geometric optics. The wave nature of light rays invariably obeys the laws of physics, and nothing can be done about it. The smaller the aperture, the greater the diffraction effect and the lower the sharpness of the output image. In addition, diffraction will worsen as the size of the individual sensor cells of digital cameras decreases. The macro photographer has virtually the only means of maximizing the sharp image space - the correct position of the camera relative to the subjects. Famous macro photographers advise learning to think in planes. You should always decide which parts of the tiny model you want to be extremely sharp in the photo and position the camera parallel to them. The further the camera is offset from the axis of the object plane, the more effective sharpness will be wasted on areas that do not contain any significant visual information. The body of an insect is ideal in its completeness, a wonderful product of nature. But it's not flat. It can be made completely flat, for example, by an accident in the form of the sole of a person’s shoe falling on the poor beetle’s head. Then, photographing this cake from above at f/22, you will indeed get a sharp frame. A little about the relationship between the focal length of the lens and the level of depth of field. In general, as it increases, the depth of field decreases. Only if you do not take into account the scale of the photo. That is, a 200 mm lens placed next to a 100 mm lens will reproduce a smaller angle of view and, as a result, enlarge the picture to larger proportions, losing depth of field. However, if the 100mm lens is moved closer to the subject so that both glasses provide the same magnification, their depths of field will be equal. Therefore, whatever one may say, long-focus macro objects are more useful in field conditions.

The tripod is the head of everything

But also harder. And it’s more difficult to get a sharp shot with it, if only because it requires shorter shutter speeds. Remember, the shutter speed should be approximately equal to the focal length? But where can you get them if, when shooting macro, you often have to work at the lowest levels - among the grass, hidden in the shade of bushes, in turn, nestled in the canopy of a tree. There is not enough light, and the apertures are narrow. You have to compensate by using a longer shutter speed. And you can’t do it without a tripod. Although, of course, by the time you install it, secure the camera, build the necessary lighting scheme, all living things in the area will scatter in different directions. However, patience is one of the main personal assets of a person who is interested in insect photography. Not sure about the strength of your hand? Then only a tripod. What nuances might there be? For starters, the height of the tripod. You probably won't need one that's too tall (and expensive). You need something very durable and preferably not too heavy (which is still synonymous with the definition of expensive). The famous Gitzo carbon series immediately comes to mind. This material, in addition to being lightweight, also does not freeze in extreme cold. The diameter of the tripod legs should not be too narrow. Tripod stability should not be compromised. It is desirable that the legs of the tripod bend at as wide an angle as possible, approaching 90?. After all, it is necessary to ensure its position is as low as possible and turn the camera along with the L-platform 90°. Since we're talking about tripod accessories that make macro photography easier, let's mention another useful thing - focusing rails. When focusing a macro lens, individual lenses move inside it along the axis of the helicoid - the helical surface. This increases the distance between the optical center and the plane of the film/matrix, which, as we have already found out, leads to an enlargement of the scale of the depicted object. In the realm of macro proportions, any minor inaccuracy will result in a ruined photo frame. It is safer to manually focus on some accessible object located in the plane of our model, and then simply move the camera along with the lens, thus bringing the focus to the required limit. Photographers often resort to using special rails with millimeter markings. They are placed between the tripod head and the camera. By loosening the side controls, it is possible to bring the camera closer to the bug a little at a time with high precision, controlling the focus through the corner viewfinder.

Give me a hobby!

When shooting with a DSLR camera, an angular viewfinder, this periscope is an indispensable thing. You don’t have to bend over backwards to get your eye to the eyepiece of the camera’s standard viewfinder. For those who work with medium format cameras, it is easier to create a macro frame by looking through a shaft viewfinder. In this regard, digital compact models with a non-replaceable lens are also convenient - those with a flip-out LCD display. However, as we have already found out, the macro attachments available for them are not the most acceptable way to achieve an increased scale. Owners of compact cameras should sometimes consider using a teleconverter. In principle, its main purpose is to increase the focal length of the lens. With the same working shooting distance, a lens with a teleconverter will provide a larger scale by enlarging the central part of the image. Let's say, if we take the popular Sigma 180 mm f/3.5 macro lens with a minimum focusing distance of 46 cm and a working distance of about 23 cm, then after attaching a 2x teleconverter to it, the focal length will increase to 360 mm with the same lens magnification (1:1 ), and most importantly, the available working distance will double. If you shoot at a “normal” distance for this lens, 23 cm, the scale will reach 2:1. True, the teleconverter reduces the lens aperture exactly as much as it increases its focal length. 2x 50mm teleconverter for 3x zoom. It is advisable to choose the fastest possible lens as an attachment lens to avoid excessive vignetting. Zoom lenses are not suitable for these purposes. The new working distance of such a connection will be equal to the working distance of the additional lens. As for the adapter (in English it is called a coupling ring), it is quite possible to make it yourself. Take two old filters for the threads of one and the other lens, knock out the glass from them, glue them together, making sure they are opaque, and carefully screw them onto the lenses. Many people like to experiment with so-called “reversing rings”. These are also adapters, but they are attached directly to the mount of a SLR camera. A regular lens is used, only turned upside down so that the bayonet mount points outwards. Keep in mind that with this mounting option, the camera’s exposure metering function disappears. Perhaps the most popular accessory used to increase the scale of macro photography are extension rings in all their variety, which are also located between the bayonet mount and the lens. There is no high-tech exoticism in them, just ordinary hollow metal extensions that look like pipe scraps. Despite their relative cheapness, these rings are quite effective way upscaling. Its extent will depend on the length of the ring, which simply moves the optical center of the lens further away from the film/sensor plane. The additional magnification achieved through the use of extension rings is equal to the ratio of their total length to the focal length of the lens. It's easy to see that short focal length macro lenses coupled with extension rings will give you greater zoom. The disadvantage of the latter is the reduction in the amount of light entering the film/sensor, since the diameter of the aperture in relation to the total focal length of the lens + extension rings combination decreases. TTL metering on digital SLRs will take light loss into account, correctly calculating the required exposure.

And let the light shine on the bug

Let it spill, just be very careful. The insect is small, and its body may be covered with a highly reflective, reflective shell. Especially beetles that hide their wings under it. Lighting in macro photography is a whole science, or, if you like, an art. And here the craftsmen came up with so many things that they could devote a special issue of the magazine to the topic. Let us determine the main problems of lighting spider beetles, winged and buzzing. They all move, constantly in some search (maybe the meaning of life?), and even a beetle frozen on a leaf, carefully watching you, assessing whether you are worthy of being posed for you, may have its mustache moving, twitching nervously paw or something. If you don't achieve a fast enough shutter speed, some part of the model will be blurred. But the wide aperture required for this will plunge the “portrayed” into the darkness of blur. We close the aperture and increase the shutter speed, and even in the context of using all these light-cutting attachments, extension rings, and bellows. Suppose we are lucky enough to find a photogenic insect that seems willing to play the role of a patient model, perched on the upper tier of grass vegetation facing the sun. It’s naturally summer outside or, at the very least, warm autumn. The midday sun creates striking black and white contrasts. Our task is to optimize flows sunlight, change its quality.

For example, create diffuse lighting from hard contrasting light. Companies like PhotoFlex or Lumiquest make special diffusers that are essentially a disk with clear nylon stretched over it. Its effect is similar to shooting on a cloudy day - the resulting soft light is more evenly distributed over the frame area, smoothing out small light-and-shadow imbalances. The diffuser should be kept as close to the insect as possible, blocking the direction of incidence of sunlight, naturally, so that it itself does not fall into the frame. A diffuser placed too far from the subject will have virtually no effect, creating an unnecessary shadow in the frame. While taking care of uniform illumination of the main subject, keep an eye on the background, which may be in the shadows or, conversely, subject to harsh overexposure, distracting attention in the image. In the first case, a complementary diffuser-reflector will help, in the second, say, it is reasonable to use a second diffuser or, if the light is too bright, try to obscure it with your shadow. The "factory" reflector has the same design as its counterpart, but instead of transparent nylon, it has a shiny metallic or yellow foil-like surface. The reflector must be handled very carefully - the amount of light it sends to the object can be excessive, especially if the object is an insect with smooth shiny surfaces. In such cases, it is advisable to direct the beam of light parallel to them, allowing only light contact with the beetle's shell. It’s clear that in order to work with these accessories, you need to have both hands free – a tripod will help out. However, diffusers and reflectors are effective when shooting relatively static scenes. You can try using a compact version of the diffuser mounted on an external flash.

Flashes... The working distance to the photographed insect in macro photography is very small. The pulse of the external and built-in flash is quite strong, and when using the latter it is easy to get a shadow from the lens, especially when shooting at large scales. Apart from standard flashes, there are two types of special flashes for macro photography. These are ring and two-lamp, mounted on movable brackets. The first ones, in general, are not exactly macroflares in their essence. At least they are not suitable for creative macro photography. They were originally developed for the needs of medicine and science. As its name suggests, a ring flash consists of several small sources grouped in a circle. Unfortunately, unlike its power, the direction of light of a ring flash cannot be changed, and therefore it is not so widely used. Judging by the reviews, many photographers find the results of ring flashes unnatural, too sterile and laboratory-like. The insect may appear “plastic”, taken out of the context of its natural habitat. And the “context” itself, ring flashes lead into deep shadow.. Another thing is double flashes on independent brackets, like the Canon MT-24EX Macro Twin Lite or Nikon SB-R200. In such flashes, the mounting ring is attached directly to the edge of the lens, and the control unit is located in the hot shoe socket. From here, via the LCD display, you can control the flash power, its compensation and other user functions. They are a successful find for manufacturers, a standard of technical thought in the field of macro lighting.

Each has its own approach or “Beware of bees!”

Still, no matter what you say, it has become easier to live with numbers - without irony. Free images allow you to take as many test shots as you like, checking the performance of a particular optical chain or lighting in macro photography using the LCD display and histogram. But the complexity of the macro direction itself, especially its entomological wing, should not be underestimated. Many believe that, in addition to deep technical knowledge, it also requires remarkable biological erudition, and, in general, broad knowledge of natural science. For example, it is important to understand that the most favorable time for shooting is early in the morning in good weather. At this hour, insects that have absorbed the moisture of the night appear on the branches and leaves of trees, and, half asleep, expose their wet wings, mustaches, and backs to the sun. Windy moths and butterflies slow down somewhat in their elusive playfulness towards evening. Praying mantises and ladybugs are relatively immobile and can be “taken” at almost any time of the day. But flies, wasps, bumblebees are a living hell, especially in the midst of a stuffy and sunny summer day. Most spiders are blind, making them easier to approach without being noticed. True, in tropical forests you can’t joke with spiders - there are a lot of poisonous ones, you don’t know who you’ll run into. After all, according to scientists, there are several million undiscovered insect species left on Earth! Dragonflies also require a careful approach. They, of course, will not bite you, but they will disappear from the camera lens in the blink of an eye. Unless the couple makes love. Dragonflies have a long body, so try to shoot at the narrowest apertures possible so that it all falls into the zone of sharpness. As a last resort, the eyes of this fast-winged insect should always be clearly in focus. Dragonflies immediately fly away when they notice your approach. Don't despair, position your macro kit near the grass stem. Today is a fine day - the dragonfly will definitely return. And then you will need to act quickly. Her most photogenic pose - upright with her wings raised - is maintained for a second during landing.

When the sun has just risen high enough, butterflies offer their wings to it. Having dried them, they begin their daily affairs with enviable efficiency. This is to your benefit - the butterflies will not pay much attention to you. It's good to have a long macro lens and a firm hand: Shooting winged beauties does not require extremely narrow apertures. They themselves are quite flat, especially with the wings folded, and with a good shooting angle they can be completely in the sharpness zone already at f/5.6-f/8.

Bees... There is a special conversation about them, but at this stage it is better to avoid them and not interfere with dragonflies making love. By the way, do not forget to turn on the mirror pre-raise mode before releasing the shutter of your SLR camera.

© Lindsay Silverman, D300S, AF-S NIKKOR 85mm f/1.8G, 1/100 sec, f/8, ISO 200, aperture priority, matrix metering.

© Diane Berkenfeld, D800, AF-S DX NIKKOR 18-300mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR, 1/500 sec, f/16, ISO 1400, aperture priority, matrix metering.

© Christina Kurtzke, D3S, AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8G ED, 1/800 sec, f/2.8, ISO 800, manual exposure, matrix metering.

© Christina Kurtzke, D3S, AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8G ED, 1/640 sec, f/2.8, ISO 800, manual exposure, matrix metering. Since the subject was not shy, the photographer was able to convey the scale of the shooting by capturing a butterfly resting on his finger.

Science knows of more than a million species of insects living on our planet, and many of these tiny creatures can be found right on your doorstep. By the way, all insects belong to the phylum arthropods. Distinctive features The insect's features are a segmented body, six legs, two antennae, compound eyes and in some cases wings. There are other creatures, such as spiders and scorpions, that are also arthropods but are not insects. Photographing insects and other miniature creatures can be a lot of fun. You don't have to stray far from home to discover a whole new world with macro photography.

The first of the basic rules of macro photography is to get closer to the subject. To photograph insects, you need a macro lens that allows you to focus very close to the subject. Using a macro lens (such models produced by Nikon are called Micro-NIKKOR) you can photograph miniature objects almost life-size.

You will also need a tripod to keep the camera steady. This is especially important when using a telephoto lens or slow shutter speed. If the camera is mounted on a tripod, the ideal shooting method is to release the shutter using a cable release. Some DSLR photographers also lock the mirror in the up position before releasing the shutter. This further improves the camera's stability. If you don't have a cable release, you can use the camera's self-timer mode instead.

Depending on the shooting distance, you can capture the entire insect or some part of its body, such as its head or antennae, in the frame. Be careful: many insects bite!

© Lindsay Silverman, D3, AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8G IF-ED, 1/30 sec, f/11, ISO 200, aperture priority, center-weighted metering.

© Diane Berkenfeld, D600, AF-S DX Micro NIKKOR 40mm f/2.8G, 1/100 sec, f/5, ISO 800, programmed exposure, matrix metering. Slow-moving insects like this mantis are great for photography. The photographer managed to follow him as he walked around the fence and took a whole series of shots from different angles.

© Diane Berkenfeld, D600, AF-S DX Micro NIKKOR 40mm f/2.8G, 1/1600 sec, f/10, ISO 800, aperture priority, matrix metering. When shooting with a 40mm macro lens, you need to get close to the subject, but most insects do not pay attention to the proximity of the camera (and the photographer) when collecting nectar.

© Diane Berkenfeld, D600, AF-S DX Micro NIKKOR 40mm f/2.8G, 1/1250 sec, f/10, ISO 800, aperture priority, matrix metering. If you don't want to take the risk of photographing insects with a macro lens, you can start with creatures that won't bite you. The shorter the focal length of a macro lens, the shorter the actual distance to the subject should be, which must be taken into account when choosing a lens for work.

Insects have incredible bodies, and one of the goals of nature macro photography is to show their amazing lives in all its color and detail. To get a good macro photo, the photographer focuses on the eyes, legs and bodies of these tiny creatures, as well as the details of their miniature world. For example, a photograph of a spider lurking in the center of a web may tell a more interesting story.

The background color plays an important role in the composition. If the subject of photography has a dark color, which is characteristic of many insects, then against a light, blurry background it will stand out well and attract the viewer’s attention.

A technique that allows you to highlight an insect against the surrounding background is to use a shallow depth of field of view. Depth of field is the size of the in-focus area in front of and behind the main subject. The depth of field in the image is determined by the aperture setting. Small apertures such as f/2.8 result in shallow depth of field, allowing you to accurately focus on your subject while leaving the background out of focus.

Another technique that photographers use is to shoot a brightly lit subject against a dark background. If you expose a well-lit subject, such as in bright daylight or with fill flash, the dark background will be underexposed and appear almost black. This allows you to get a uniform dark background against which the object will stand out clearly.

But if both the subject and the background are brightly lit, the insect may be difficult to distinguish in the photo. In this case, you can place an object behind the insect, such as a piece of fabric or a sheet of paper, which will act as a portable studio background and help highlight the object and make it distinguishable.

Insects are more active in warm weather: photograph them early in the morning or evening when it is cooler and they will be slower. Natural light at this time of day is also more advantageous.

© Christina Kurtzke

D3S, 1/1000 sec, f/5.6, ISO 200, manual exposure, matrix metering. This is the same shot of a bee on a flower as on the left, but after cropping. The image can be composed as you shoot, but you can also crop it or otherwise experiment with it on the computer.

One of the most exciting aspects of photography is that it opens the door to worlds that we cannot see with the naked eye. Trying to capture these worlds presents its own challenges and requires a much more systematic approach than other areas of photography, but the results are exciting and worth the effort. Macro photography of the most numerous but least noticeable creatures of our planet - insects - great example this.

For achievement best results, you need to use a technique known as taking multiple shots of the same subject with the focus point slightly shifted, and then stitching their sharp areas together in order to create a highly detailed final image.

Preparing for macro photography using the stacking technique

You can easily photograph insects on your desk at home.

It is important to keep in mind that the composition of each photograph must be the same so that at the photo processing stage, the program can easily create the final image. To achieve this, you must first prepare properly for the shoot.

You will need a spacious workplace, where no one will disturb the order of your equipment, and there is enough space to move without the risk of accidentally touching something. At a minimum, you need a heavy tripod and a sturdy table that won't move.

Before shooting, I stress test my equipment - I take my hands off the tripod and don't support anything. All equipment must remain in place and nothing must fall or be damaged.

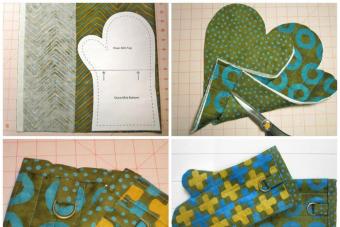

To achieve close focusing, you can use a set that are installed between the lens and the camera. They can be bought quite cheaply. A simple 50mm fifty with macro rings is a good starting option as a macro lens.

Composition in macro photography of insects

A good composition is what will help you create not just photos for scientific articles, but more attractive pictures that bring aesthetic pleasure.

Insects are removed from the lowest point, this makes it more dynamic. Think about how your photo will be read. Insects' eyes and mouths make a fantastic focal point, and claws, mandibles and hair can be used as powerful anchor points.

When preparing to shoot, leave as much space around your subject in the frame as possible. Remember that you will have to force it, because the macro rings will produce on the periphery of the frame.

When you stitch photos in the program, you will find that the program will align your cropped images well. Therefore, the more space you give yourself, the more flexibility you will have to create the final pleasing composition. In such cases, a camera with a high matrix resolution, such as my Sony Alpha 7R II with a 42.4 megapixel sensor, will come in handy.

Stacking technique for macro photography

Macro rail helps you fine-tune your focus

Consistency is the key. The goal of stacking is to create a series of similar images in which the focus changes just ever so slightly to give you enough material that can be stitched together on the computer to achieve the desired depth of field in the final image. You can do this by moving the camera very small distances, either towards or away from the subject, using . Manually adjusting focus using the focusing ring on the lens in such cases is almost impossible.

Position the camera as close to the subject as possible so that you move away from it rather than closer. This way, you don't have to worry about accidentally touching the equipment, disturbing an insect, or ruining the shot. Use the self-timer cable or set your camera's timer to ensure there is no shake when you press the shutter.

Take as many images as possible while moving the macrorail slightly. You may not use all of these photos for staking, but it's good to have a lot to choose from. Adjust your exposure manually, otherwise you risk getting different shots.

To get the desired effect, it is important to use a flash, because when shooting at closed apertures there is not enough natural light. Fortunately, since insects are very small, a regular external flash will work well.

Place the light on a small tabletop tripod as close to the subject as possible and experiment. Give the flash enough time to recover between shots. If the lighting is not the same, it will not be possible to combine the frames. Once you get comfortable with the technique, you can experiment a little. As with a camera, it is better to set the flash in manual mode.

To start, take 20-30 images at f/11 and make sure that the sharp area in the pictures is moving. Later, you can use a smaller aperture and get sharper images by taking more shots, but the depth of field will be shallower. Ultimately, you should aim to use the aperture that your lens is sharpest at, usually f/ 4 - f/ 5.6. To do this, you may need 100 shots to get the same sharpness in all areas of the frame.

Processing and stitching of captured photographs

The Helicon Focus program allows you to export the final result to a source file. These programs are not easy to learn, so don't be discouraged if you don't get the results you expect right away. The radius and blur settings can be very different for each image, and you can only find the best ones through experience. But over time you will get the hang of it.

Photo aesthetics when stacking

When you create images using stacking, sometimes it's tempting to forget about aesthetics and just stitch together 500 photos to achieve perfect sharpness.

This method can be tempting, but more often than not it doesn't create a truly captivating image. You must not forget that the truly good images are those that manage to capture a story. For example, when I photographed a common house spider (see photo above), I decided to put a strong focus on its eyes and fangs to convey the spider's liveliness and movement - and this photo was created by combining just two photos.

Lighting arrangement for macro photography of insects

For this ladybug photo the setup was pretty simple, the key was choosing the background. The bright color and threads from the scarf created a beautiful backdrop for the subject. I used two trigger flashes - one with a colored gel, the other covered with white cardboard to soften the main light. And I placed another sheet of white cardboard to the left of the camera to fill the shadows with reflected light.

Experiment with the background

As you become more experienced with stacking techniques, you can try using colored gels or cardboard to really bring your photos to life with interesting lighting and backgrounds.

Use a dedicated staking program

A specialized program like Helicon Focus will allow you to link your source files together, so when it comes to post-production you have a lot of options. Experiment with combining files, work with JPEGs before moving directly to the sources.

In order to stitch images, the Helicon Focus Pro program is used.

Cool the insects

After death, the bodies of insects decompose extremely quickly, so it is best to photograph them alive - but you must not let them move. For filming, it is best to lower their body temperature so that they begin to fall asleep and their movements slow down. How long to keep insects in the refrigerator (or freezer) depends on their size and weight. Place them in a plastic container and check every 1-5 minutes to see how much their movements have slowed down.

Macro Photography Equipment Used

Sony Alpha 7R II

Since stacking requires a lot of cropping, a camera with more megapixels will give you a great opportunity to do this and still produce large, printable files. The full-frame Alpha 7R II can produce very clear and detailed images with the right lens.

Macrorelsa

It is almost impossible to make subtle shifts in focus when using the lens. A macro rail will give you the ability to move your camera very short distances, giving you the ability to take smooth focus shots that are good for stacking.

Flashes

Flashes will allow you to use small apertures and low ISOs. A low ISO will give you less noise and more room to adjust colors and exposure in post-processing. Also, you need the same lighting in all photos in order to combine them later, which is not always possible with natural light.

Helicon Focus Pro program

Although you can stitch photos together in another program, I highly recommend you use this one because it allows you to create a source file from the final stack, giving you more editing options.

The author of the article is Mikael Buck, a London-based editorial and commercial photographer. He worked for over ten years as a photojournalist for publications such as TImes, Mail on Sunday and The Metro. Currently works on a commission basis for British national publications, high-profile companies and major brands.

Wasps

Tip #1

Even if you are not allergic, when planning to remove wasps, keep anti-allergy medications with you. You can easily endure a wasp sting, but if you accidentally frighten an insect, it will instantly transmit an alarm signal to all wasps nearby. In this case, you risk becoming the target of an entire nest of wasps.

Tip #2

Do not smoke when photographing wasps, do not wear perfume before taking photos. Clothing should cover the body as much as possible. The sleeves have cuffs so that the wasp cannot fly into the hole.

Tip #3

Do not wear woolen clothes. A wasp can easily become entangled in the hairs. Be sure to cover your neck. Bites to the neck are the most dangerous. A hat is also required. Hair must be completely tucked under a cap or hat. Wasps often get entangled in hair and, when frightened, sting.

I was stung three times in August last summer. The first time a wasp got entangled in the wool of a sweater. The other two - carried away by filming, I reached for a syringe with bait, grabbed it without looking, and got bitten. Unpleasant...

Bees

They say fools are lucky. This is my case. In one day of shooting, I managed to break all the existing rules for working with bees. Thanks to Sergei Talanov, I learned in time that I had acted extremely imprudently and stopped dangerous experiments.

In this photo, bees are preparing to attack. How can you figure out who is the object of interest for the army of bees? I left the hive literally a minute before the attack, not understanding the threat that loomed over me.

I filmed while standing in front of the entrance to the hive in the rain, which caused terrible discontent among the bees.

You cannot stand in front of the entrance, much less lay out equipment, set up a tripod, etc.

Clothing, as when photographing wasps, must be appropriate (see information about wasps)

Antiallergic medications should always be on hand.

Ticks

These microscopic creatures can cause a lot of trouble. Ticks are carriers of diseases such as encephalitis, borreliosis and others. I won’t tell you horror stories, but believe me, there aren’t many good things.

So clothing for macro hunting must be appropriate. Anti-tick suits are now on sale. I don’t know how reliable they have proven to be, but I prefer camouflage and soak it with anti-tick sprays.

wild nature

Wildlife... is wildlife. As long as you are photographing flowers at your summer cottage, everything is fine. But sooner or later you will want to get out into the forest, and, in search of new places to shoot, wander deeper.

That's exactly what I did. Well, what can we take from a Muscovite who travels to maximum pioneer camps in childhood? When a polite, quiet growl is heard behind you, in complete silence, it’s scary. I came across an educated bear. He behaved exactly as indicated in the instructions on the Internet about the correct behavior when meeting wild animals. The bear clearly read the memo. Me not.

Even more imprudent on my part was the decision to wander through the oat field. Well, how? Ears of corn, sun, aroma, nature and so on, so on. Then I saw wild boars for the first time in my life. Mom, dad and kids. I think you will believe me that I have probably broken all possible running records. Fortunately, for short distances. The jeep was standing nearby...

Remember: a bee, a wasp, an ant, a bear or a wild boar - they are all in their own territory. And we are visiting. Don't forget about this and everything will be fine!

Good luck to you!

about the author

about the author

Technique: Pentax K10D, SMC PENTAX-DFA MACRO 1:2.8 100mm WR lens

Last week we also started a topic. It's time to continue it and talk about the features of photographing various insects.

First of all, in continuation of the previous part, I would like to offer some technical tips:

1. When taking macro photography, use a protective filter. Flowers and butterfly wings contain pollen, an active chemical that can damage the anti-reflective coating on your lens. For this purpose, it is recommended to use the simplest and most inexpensive UV filter.

2. When shooting close-up macro in good, sunny weather, in most cases you have to shoot in backlight. To avoid the possibility of glare, we advise you to use a lens hood.

3. Take care of the background. A dark background looks advantageous, but good lighting of the object itself is necessary. A light background is used in cases where it is necessary to show the silhouette of the subject, while the background itself must be well lit. A colored background works on the contrasts of warm and cool tones, for example, “squeezing” objects of warmer tones into the foreground. A gray background works well to highlight the color of the main subject.

Habits of insects

Experience will teach you to assess the situation in advance and selectively approach the selection of objects. For example, on clear, sunny days, look for insects resting on the tops of plants. This will help you avoid distracting shadows among the foliage. Look carefully at the background and try to choose objects that will be clearly visible against the dense stems. It's not always possible, but

As a compromise, carefully select your depth of field and slightly lower magnification, so you can better control the composition and later frame the photo.

On clear, sunny days, look for insects high on vegetation stems, as you won't have to deal with heavy shadows there. Use longer lenses with extension rings on very clear or hot days to increase the working distance from the lens to the subject. This is only practical when photographing large insects at a magnification factor of up to half natural size.

Inspect Apiaceae inflorescences as they attract small beetles and insects. Early in the morning, visit the banks of small ponds and creeks where dragonflies may be hiding.

Don't limit your shooting time to the middle of the day, when air temperatures are highest; Go on a photo hunt very early in the morning or in the late afternoon when it gets cooler. You may be able to find insects that are more tolerant of your presence.

On cloudy, gloomy days, when the air temperature is not so high, it is worth looking among the ground vegetation for large insects, which often rest, hiding among the leaves and grass. It is often possible to shoot from a tripod, unless you notice nearby vegetation.

One wrong move and the object will jump off and disappear into the grass. With more high temperature insects become active, and it is more difficult to approach them unnoticed.

Working with insects that rest for long periods on plant stems can be more productive, especially while you are honing your skills. Many experienced insect photographers will tell you that it's all about a skillful combination of field skills and observation.

Butterflies

Butterflies, like many other insects, are attracted to light. They are regular visitors to the gardens; Some of the larger species, such as hawk moths, are often targeted by photographers due to their attractive colors.

Bright light falling from an open bathroom window on a warm, humid night in summer will attract moths and other insects into the room.

Caterpillars

Caterpillars (larvae) of butterflies are more careful than their adult relatives. Some can be discovered by chance from time to time, but most are hidden so that they are rarely noticed at all. You can find the most common species by carefully inspecting the leaves and branches of low trees and shrubs.

Filming caterpillars can get quite tedious. Once you disturb them, they curl up, and a lot of time passes before they unfold again. It's best to leave them alone to settle in whatever way is most comfortable for them.

Dragonflies

Many consider dragonflies to be one of the most attractive insect species. Their rainbow colors and aerial piloting skills make us especially happy.

A small pond in the garden will certainly be of interest to the most common types of dragonflies, however, most of them require very specific living conditions.

Wetlands, ponds and other freshwater bodies are the most common places where you will be able to see and photograph dragonflies. Early rise and careful inspection of the vegetation around a small pond or secluded lakeshore often reveals resting adults that had roosted the night before.

Darter dragonflies are much more common than large dragonflies. They rest in whole flocks, and it is much easier to find them. If the air temperature drops below the threshold for their flight to begin, these insects remain motionless until it warms up, so you can get closer and even use a tripod.

Many dragonflies and butterflies have distinctive habits, and patience and careful observation will reveal their traditional behavior patterns.

Some butterflies prefer specific flowers and will ignore others, while certain dragonflies will invariably return to one or another isolated “favorite” blade of grass near a pond or stream. Even a basic understanding of your targets' behavior and habits will help improve your chances of success.

Grasshoppers and crickets

Most often, these are summer species found in many habitats. They spend most of their time among dense vegetation. The easiest time to find them is on warm sunny days, when the males begin to “sing”, rubbing various parts of their bodies against each other. This behavioral detail is known as chirping or stridulation. A clearly distinguishable sound is characteristic of each species; soon experience will help you recognize insects by their “voice”. Scare them out of low vegetation and try to get them to move out into a more open area where there is a better chance of getting a good photo.

Beetles, mayflies, hoverflies and leafhoppers are equally attractive, but due to their small size are much less known. They can be found when they appear on inflorescences or resting among vegetation, where it is worth looking closely at them.

Subjects

Insects transform from eggs to larva, from larva to pupa, from pupa to adult insect. All this is called metamorphosis. You can get an interesting series of images of this process, although it will take a lot of effort to find the subject in nature at various stages.

Some lovers of macro photography of insects get out of this situation by independently “growing” insects that will become the subject of photography.

One option for creating conditions for filming is to plant a plant that will become food for the larvae.

In the process of insect growth, the most interesting moment is probably the moment the wings appear. There are insects such as butterflies or horned beetles that become adults from pupa (complete metamorphosis), and dragonflies and cicadas that directly become adults from larvae without going through the pupal stage (incomplete metamorphosis). Either way, the transformation is dramatic.

Shot on Nikon D3100, NIKKOR Helios 44-2 and macro rings

If you want to create a true work of art, then you need to add the environment to complete the picture. Let’s say, if we take a butterfly as an example, then the presence of a flower in the frame will create not just a photograph of a butterfly, but a full-fledged scene in which the surrounding background will competently complement the main object, allowing you to raise your photo to a higher level.

There are many ways to photograph insects, but unfortunately there is no specific technique that will work in every situation. There are many factors to consider, such as the size and habits of the insect, the equipment you have at your disposal, and the weather conditions at the time. It is very important to learn to observe the behavior of various insects in order to be able to take successful photographs in the field.

The most efficient approach is to concentrate your efforts on one group of insects at a time; This will help you gain experience and confidence in using your camera equipment.

Traditional thanks to the photographers who provided photographs for this publication, viz.